Feelings List: A Complete Guide to Emotions for Mental Health & Self-Awareness

Key Takeaways: Feelings List – A Complete Guide

A feelings list gives you the words to recognize and express emotions more clearly.

Naming emotions helps reduce stress, improve communication, and support mental health.

Children and adults alike benefit from using feelings lists for emotional awareness.

Men often struggle more with talking about feelings, making this tool especially helpful.

Daily use of a feelings list builds stronger self-awareness and healthier relationships.

Most adults can easily identify when they feel hungry, tired, or stressed, but struggle to name the subtle differences between disappointment and regret, or distinguish between anxiety and excitement. This gap in emotional vocabulary isn’t just a minor inconvenience—it’s a significant barrier to mental health and self awareness that affects millions of people daily.

Your ability to understand and articulate your emotional states directly impacts your psychological well being, relationships, and overall quality of life. When you can accurately identify what you feel, you gain the power to address those feelings constructively rather than being overwhelmed by them. Emotions can happen unexpectedly or spontaneously in response to various situations, and recognizing when these emotions happen is the first step to managing them.

This comprehensive guide will provide you with an extensive feelings list and the knowledge to use it effectively. You’ll discover the science behind emotion classification, learn to distinguish between basic emotions and complex secondary feelings, and develop practical skills for improving your mental health through enhanced emotional intelligence.

Complete Feelings List: 270+ Emotions Quick Reference

Use this comprehensive emotions chart to identify and name your feelings. Each category includes intensity levels to help you pinpoint exactly what you're experiencing.

💾 Download this complete feelings list as a printable PDF

Download Free PDFUnderstanding Emotions: The Foundation of Mental Wellness

The ability to recognize and name emotions serves as a cornerstone of psychological science and therapeutic practice. When a person feels distressed but can only describe their experience as “feeling bad,” they miss crucial information about their internal state that could guide them toward appropriate coping strategies.

Emotional awareness leads to better self-regulation because naming an emotion activates the prefrontal cortex, which helps dampen the intensity of limbic system reactions. This process, sometimes called “name it to tame it,” transforms overwhelming sensations into manageable experiences that you can address systematically.

The difference between feeling emotions and understanding them lies in your capacity to move beyond basic awareness to detailed recognition. While everyone experiences the full spectrum of human emotions, many people lack the vocabulary to distinguish between related but distinct emotional states. This limitation restricts their ability to communicate needs, seek appropriate support, and develop targeted solutions for emotional challenges.

Adults often struggle with emotional vocabulary despite experiencing complex feelings daily because our education system traditionally emphasizes cognitive development over emotional literacy. Many people learn to suppress or minimize emotions rather than explore and understand them, leading to a disconnect between their rich inner experience and their ability to describe it.

Once you’re familiar with different emotions, try using the Feelings Wheel to visually explore how emotions connect and deepen your self-awareness.

The Science Behind Emotion Classification

Paul Ekman’s groundbreaking research identified universal emotions through cross-cultural studies of facial expressions, leading to his Atlas of Emotions framework. His work with over 100 scientists distilled human emotional experience into five major categories: anger, fear, sadness, disgust, and enjoyment. This model suggests that these basic emotions appear consistently across cultures and serve fundamental evolutionary purposes.

Robert Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions expanded this understanding by organizing emotions in a circular model that shows relationships between different emotional states. His framework demonstrates how primary emotions can combine to create secondary emotions, much like primary colors mix to form new hues. The wheel illustrates intensity levels, with emotions ranging from mild variations to intense expressions along two axes of evaluation and activation.

The debate between discrete emotion theory and dimensional models continues to shape psychological science. Discrete emotion theory proposes that emotions are distinct categories with specific triggers and responses, while dimensional models suggest emotions exist along continuous spectrums of arousal and valence. Recent research indicates that humans may experience as many as 27 discrete emotion categories, far exceeding traditional basic emotion models.

Neuroscience reveals fascinating connections between emotions and physical sensations. The insular cortex processes both emotional states and bodily awareness, explaining why you might feel anger as heat in your chest or anxiety as tightness in your stomach. Understanding these mind-body connections helps you recognize emotional states through physical cues, creating multiple pathways for emotional awareness.

Core Primary Emotions: The Building Blocks

The six primary emotions—joy, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust—form the foundation of human emotional experience. These basic emotions serve evolutionary and survival purposes, appearing early in human development and manifesting similarly across cultures. Each primary emotion carries specific physical manifestations and typical triggers that help you identify them accurately.

| Emotion | Physical Signs | Common Triggers |

|---|---|---|

| Joy | Lightness, warmth, increased energy, relaxed muscles | Achievements, connection, pleasant surprises |

| Sadness | Heaviness, low energy, tears, muscle tension | Loss, disappointment, separation |

| Anger | Heat, tension, clenched muscles, increased heart rate | Injustice, boundary violations, frustration |

| Fear | Rapid heartbeat, shallow breathing, muscle tension | Threats, uncertainty, perceived danger |

| Surprise | Raised eyebrows, widened eyes, brief muscle tension | Unexpected events, new information |

| Disgust | Nausea, facial tension, recoil response | Contamination, moral violations, offensive stimuli |

Understanding these foundational emotions provides a framework for recognizing more complex emotional states. Each basic emotion exists on a continuum from mild to intense, and combinations of primary emotions create the rich tapestry of human emotional experience.

Joy and Positive Emotions

Joy encompasses a broad range of positive emotional states that share common characteristics of pleasure, satisfaction, and well-being. These emotions typically involve increased energy, a sense of lightness, and physical sensations of warmth and relaxation. When you experience joy, your facial expressions naturally brighten, your posture becomes more open, and you may feel motivated to share your positive state with others.

The variations of joy include happiness, contentment, excitement, gratitude, love, pride, relief, bliss, delight, enthusiasm, elation, cheerfulness, serenity, satisfaction, hope, optimism, amusement, and affection. Each carries subtle differences in intensity and focus. Contentment represents a quiet, stable form of joy, while excitement involves high energy and anticipation. Gratitude combines joy with appreciation for specific benefits or experiences.

Physical sensations associated with positive emotions often include a sense of expansion in the chest, relaxed facial muscles, and increased overall energy. Some people describe feeling “light” or “buoyant” when experiencing joy. These sensations can help you recognize positive emotions even before you consciously identify them.

To cultivate and maintain positive emotional states, focus on activities and thoughts that naturally generate these feelings. Regular gratitude practices, engaging in meaningful relationships, pursuing personal interests, and celebrating small accomplishments all contribute to emotional well being. Remember that positive emotions, like all emotions, are temporary experiences that naturally fluctuate throughout your life.

Sadness and Grief

Sadness serves important psychological functions, signaling loss and prompting behaviors that help you process difficult experiences and seek support from others. This primary emotion manifests through various physical sensations including heaviness in the chest, low energy, tears, and a general sense of deflation or withdrawal from activities.

The spectrum of sadness includes melancholy, despair, loneliness, disappointment, heartbreak, sorrow, grief, mourning, dejection, gloom, regret, misery, anguish, devastation, emptiness, and hopelessness. Each variation carries different implications for duration and intensity. Melancholy might represent a gentle, somewhat pleasant sadness, while despair indicates more severe emotional pain that may require professional support.

Distinguishing between normal sadness and concerning depression involves examining duration, intensity, and functional impact. Healthy sadness typically relates to specific events or losses and gradually improves over time. When sadness persists for weeks without relief, interferes significantly with daily functioning, or includes thoughts of self-harm, professional mental health support becomes essential.

Healthy grief processing involves allowing yourself to fully experience sadness while maintaining connections with supportive people and engaging in self-care activities. Avoid rushing through grief or trying to “fix” sadness immediately. Instead, practice gentle self-compassion and remember that sadness, while uncomfortable, provides valuable information about what matters to you.

Anger and Frustration

Anger functions as an important emotional signal that indicates boundary violations, injustice, or obstacles to your goals. This powerful emotion mobilizes energy for action and can motivate positive changes when channeled constructively. Understanding anger’s message helps you address underlying issues rather than simply suppressing the emotion.

Anger variations include irritation, rage, resentment, indignation, annoyance, fury, outrage, exasperation, aggravation, hostility, wrath, bitterness, contempt, disgust, and frustration. These emotional words represent different intensities and focuses of anger. Irritation suggests mild anger that may be easily resolved, while rage indicates intense anger that requires careful management to prevent harm.

Physical manifestations of anger typically include increased heart rate, muscle tension, heat sensations (particularly in the face and chest), and an urge for physical action. Some people clench their jaw, make fists, or feel energy surging through their body. Recognizing these early physical signs helps you implement anger management techniques before the emotion becomes overwhelming.

Constructive anger management involves acknowledging the emotion, identifying its underlying message, and choosing appropriate responses. Techniques include deep breathing, physical exercise, assertive communication, problem-solving, and taking breaks to process the emotion before responding. Remember that anger itself isn’t problematic—it’s how you express and act on anger that determines whether it’s helpful or harmful.

Fear and Anxiety

Fear serves the crucial evolutionary function of protecting you from danger by activating your body’s fight-or-flight response. This basic emotion helps you recognize threats and take appropriate protective action. Understanding the difference between rational fear and anxiety disorders helps you respond appropriately to fearful feelings.

Fear variations include worry, panic, nervousness, dread, apprehension, terror, alarm, unease, concern, phobia, paranoia, horror, anxiety, agitation, and distress. Each represents different aspects of the fear experience. Worry involves cognitive focus on potential future problems, while panic represents intense, immediate fear that may include physical symptoms like rapid heartbeat and difficulty breathing.

The fight-or-flight response that accompanies fear involves rapid physiological changes designed to help you escape or confront danger. Your heart rate increases, breathing becomes shallow, muscles tense, and your attention narrows to focus on the perceived threat. While these responses proved useful for ancestral survival challenges, they can become problematic when triggered by modern stressors that don’t require physical action.

Distinguishing between helpful fear and problematic anxiety involves examining whether the fear response matches the actual level of threat. Rational fear responds to genuine dangers and subsides when the threat passes. Anxiety disorders involve persistent, excessive fear that interferes with daily functioning and may not relate to actual current dangers.

Surprise and Wonder

Surprise serves important cognitive functions by capturing attention and facilitating learning when you encounter unexpected information or events. This brief but powerful emotion helps you quickly assess new situations and adapt your understanding of the world. Surprise can be either positive or negative, depending on whether the unexpected event is welcome or unwelcome.

Surprise variations include amazement, astonishment, bewilderment, curiosity, awe, wonder, shock, startlement, perplexity, confusion, fascination, marvel, and stupefaction. These emotional words capture different aspects of the surprise experience. Curiosity represents surprise mixed with interest and desire to learn more, while shock indicates more intense surprise that may be temporarily disorienting.

The physical manifestations of surprise typically involve brief but noticeable changes in facial expressions, particularly widened eyes and raised eyebrows. You might also experience a momentary pause in breathing, temporary muscle tension, and heightened alertness as your brain processes the unexpected information.

Cultivating wonder and openness to new experiences enhances your capacity for positive surprise and continued learning throughout life. This involves maintaining curiosity about the world, seeking new experiences, and approaching unfamiliar situations with interest rather than immediate judgment. Wonder can provide profound moments of connection with life’s beauty and complexity.

Disgust and Aversion

Disgust evolved to protect you from contamination and harmful substances by creating strong avoidance responses to potentially dangerous stimuli. This emotion extends beyond physical disgust to include moral disgust when encountering behaviors or ideas that violate your ethical standards. Understanding disgust helps you recognize both protective responses and potentially problematic aversions.

Disgust variations include revulsion, contempt, distaste, repugnance, loathing, abhorrence, disdain, nausea, aversion, antipathy, and repulsion. These emotion words represent different targets and intensities of disgust. Physical disgust might involve contamination concerns, while moral disgust relates to ethical violations or behaviors you find deeply offensive.

The protective function of disgust involves creating strong avoidance behaviors that keep you away from potentially harmful situations. When you feel disgusted, you naturally want to move away from or eliminate the source of disgust. This response can protect you from illness, dangerous situations, or harmful relationships.

However, disgust becomes problematic when it creates excessive avoidance that interferes with relationships or daily functioning. Sometimes disgust responses develop toward harmless stimuli through negative associations or cultural conditioning. Understanding the difference between protective disgust and problematic aversion helps you respond appropriately to these intense feelings.

Complex Secondary Emotions

Secondary emotions develop through combinations of primary emotions, social learning, and cultural influences. These sophisticated emotional states require more complex cognitive processing and often involve self-evaluation, social comparison, or moral considerations. Understanding secondary emotions enhances your ability to navigate complex interpersonal situations and address internal conflicts.

Complex emotional states include embarrassment, guilt, shame, envy, jealousy, compassion, empathy, nostalgia, gratitude, pride, contempt, admiration, anticipation, relief, disappointment, betrayal, loneliness, overwhelm, confusion, determination, inspiration, and vulnerability. Each combines multiple emotional elements and often involves sophisticated thinking about yourself, others, and social situations.

Embarrassment combines surprise, fear, and shame when you perceive that others are judging you negatively. Guilt involves sadness and regret about specific actions you’ve taken, while shame represents more global negative feelings about yourself as a person. Envy includes anger and sadness about others’ advantages, while jealousy adds fear of losing something important to you.

Compassion blends love, sadness, and desire to help when witnessing others’ suffering. Empathy involves sharing others’ emotional experiences while maintaining awareness of the boundary between yourself and others. These prosocial emotions enhance relationships and contribute to community well-being.

Cultural variations in secondary emotion expression reflect different values, social norms, and communication styles across societies. Some cultures encourage open emotional expression while others value emotional restraint. Understanding these differences helps you navigate diverse social environments and avoid misinterpreting others’ emotional expressions.

Emotional Intensity and Gradations

Emotions exist on a spectrum from mild to intense, and recognizing these gradations helps you respond appropriately to different levels of emotional activation. Understanding intensity helps you identify emotions in their early stages when they’re easier to manage, and it guides you toward proportional responses that match the situation.

Examples of emotional intensity progressions include: annoyed → frustrated → furious → enraged for anger; concerned → worried → anxious → panicked for fear; disappointed → sad → heartbroken → devastated for sadness; pleased → happy → joyful → ecstatic for positive emotions. Each level requires different management strategies and indicates different degrees of urgency for attention.

Using a 1-10 intensity scale helps you track emotional patterns and communicate your experience to others. A level 1-3 emotion might require simple awareness and basic coping strategies. Level 4-6 emotions often benefit from more active management techniques. Level 7-10 emotions typically require immediate attention and may need professional support if they occur frequently.

Recognizing emotional intensity serves emotional regulation by helping you choose appropriate interventions. Mild irritation might resolve with a few deep breaths, while intense rage requires more comprehensive anger management strategies. This awareness prevents under-responding to serious emotional states or over-responding to minor emotional fluctuations.

Emotional Expression: How We Show What We Feel

Emotional expression is the outward display of our inner emotional states, and it plays a vital role in how we connect with others and navigate the world. From a smile that signals happiness to a furrowed brow that reveals anger or frustration, our facial expressions are powerful indicators of what we feel inside. According to discrete emotion theory, certain basic emotions—such as happiness, sadness, anger, and fear—are universally recognized through distinct facial expressions, regardless of culture or language. This universality helps us quickly understand and respond to the emotions of those around us, strengthening social bonds and cooperation.

However, the way we express other emotions, like guilt or anxiety, can be more subtle and influenced by cultural norms. For example, while a person may openly display sadness in one culture, another might encourage masking such feelings to maintain social harmony. Body language, tone of voice, and even the words we choose all contribute to how our emotions are perceived by others.

Expressing emotions, especially negative emotions like anger or sadness, is essential for mental health. Suppressing these feelings can lead to increased stress, anxiety, and even physical health problems. On the other hand, learning to express emotions in healthy ways—such as talking about your feelings or using creative outlets—can improve well-being and help you process difficult experiences. Psychological science shows that acknowledging and expressing emotions, rather than bottling them up, leads to better emotional regulation and resilience.

Understanding your own patterns of emotional expression, and recognizing those in others, is a key step toward emotional intelligence. By becoming more aware of how you show what you feel, you can improve your relationships, communicate more effectively, and support your overall mental health.

Using a Feelings List for Mental Health

Daily emotion check-ins create awareness of your emotional patterns and help you identify triggers, trends, and effective coping strategies. This practice involves regularly pausing to notice and name your current emotional state, ideally several times throughout the day. Consistent emotional monitoring builds emotional intelligence and helps you recognize problems before they become overwhelming.

Emotional labeling reduces the intensity of difficult feelings through a process neuroscientists call “affect labeling.” When you accurately name an emotion, your prefrontal cortex becomes more active while limbic system reactivity decreases. This biological process literally helps you think more clearly and feel less overwhelmed by intense emotions.

Creating personalized emotion vocabulary based on your individual experiences makes your feelings list more relevant and useful. Pay attention to subtle emotional distinctions that matter in your life. You might notice that your experience of anxiety differs significantly from your experience of nervousness, or that your contentment feels different from your happiness.

Using feelings lists in therapy and counseling sessions enhances communication between you and your mental health provider. When you can articulate specific emotions, your therapist can better understand your experience and suggest targeted interventions. Many therapeutic approaches explicitly incorporate emotion identification as a foundational skill for mental health improvement.

Practical Exercises for Emotional Awareness

The “Name It to Tame It” technique for emotional regulation involves four simple steps: pause when you notice emotional activation, take a deep breath, identify and name the specific emotion you’re experiencing, and acknowledge the emotion without immediately trying to change it. This process helps you develop emotional awareness while reducing emotional reactivity.

Body scan meditation connects physical sensations with emotions by systematically paying attention to different parts of your body and noticing any tension, warmth, coolness, or other sensations. Many emotions manifest through physical symptoms, and developing body awareness helps you recognize emotions in their early stages before they become overwhelming.

Emotion tracking apps and worksheets provide structured ways to monitor your emotional patterns over time. These tools often include mood ratings, trigger identification, and coping strategy tracking. Regular use helps you identify patterns you might miss through casual observation and provides data to discuss with mental health professionals.

Partner exercises for improving emotional communication involve sharing your emotional experiences with trusted friends, family members, or romantic partners. Practice describing your emotions using specific emotional words rather than general terms. Ask for feedback about whether your emotional expression matches what others observe, and offer the same support to your partner.

Teaching Emotional Words: Building Emotional Vocabulary

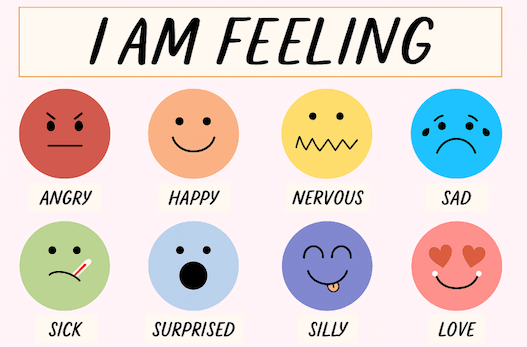

Building a rich emotional vocabulary starts with teaching and learning the words that describe our feelings. For children, this process often begins with the five basic emotions identified by discrete emotion theory: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, and surprise. These primary emotions provide a foundation for understanding and describing more complex emotional states, such as frustration, anxiety, and excitement.

Introducing emotional words in everyday conversations helps children—and adults—develop self-awareness and a deeper understanding of their own emotions. For example, instead of simply saying “I feel bad,” a child who learns to identify and describe feeling “disappointed” or “worried” gains valuable insight into their emotional experience. This ability to name specific emotions is linked to better emotional regulation, improved mental health, and stronger coping skills.

Teaching emotional words also fosters empathy and compassion. When children learn to recognize and label different emotions in themselves, they become more attuned to the feelings of others. This understanding helps them respond with kindness and support, building healthier relationships and a more compassionate outlook.

Practical ways to teach emotional vocabulary include reading books that explore different emotions, using feelings charts or emotion wheels, and encouraging open discussions about daily experiences. For example, after a challenging moment, you might ask, “Did you feel angry, or was it more like frustration?” Over time, this practice helps children and adults alike develop a nuanced understanding of their emotional states and the words to describe them.

By expanding your emotional vocabulary, you empower yourself and those around you to better understand, express, and manage emotions—laying the groundwork for lifelong emotional intelligence and well-being.

Building Emotional Intelligence Through Practice

Expanded emotional vocabulary improves relationships and communication by giving you precise tools for expressing your needs, boundaries, and experiences. When you can distinguish between feeling disappointed and feeling betrayed, you can communicate more clearly about what happened and what you need from others. This specificity reduces misunderstandings and helps others respond more effectively.

Teaching children emotional literacy using age-appropriate feeling words builds their foundation for lifelong emotional intelligence. Start with basic emotions and gradually introduce more complex emotional words as children develop cognitively. Use books, games, and real-life situations to practice emotion identification and expression.

Workplace applications of emotional intelligence include better conflict resolution, improved teamwork, enhanced leadership skills, and reduced stress. Employees who can identify and manage their emotions while recognizing others’ emotional states tend to perform better and experience greater job satisfaction. Many organizations now provide emotional intelligence training as part of professional development.

Knowing when to seek professional help for emotional overwhelm or numbness involves recognizing when your emotional experiences significantly interfere with daily functioning, relationships, or overall well-being. Consider professional support if you experience persistent sadness, overwhelming anxiety, difficulty controlling anger, emotional numbness, or thoughts of self-harm.

Common Emotional Challenges and Solutions

Emotional numbness and disconnection often develop as protective responses to overwhelming experiences or chronic stress. Recovery strategies include gradually reconnecting with physical sensations, engaging in meaningful activities, practicing mindfulness, and often working with a mental health professional to address underlying causes safely.

Overwhelming emotions require grounding techniques that help you manage intense feelings without being consumed by them. Effective strategies include deep breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, sensory grounding (noticing five things you can see, four you can hear, three you can touch, two you can smell, one you can taste), and reminder phrases that help you remember the temporary nature of intense emotions.

Cultural and gender differences in emotional expression reflect learned patterns about which emotions are acceptable to display in different contexts. Understanding these patterns helps you recognize when cultural conditioning might be limiting your emotional expression and choose whether to conform to or challenge these expectations based on your personal values and circumstances.

Breaking patterns of emotional suppression or over-reaction involves first recognizing these patterns, understanding their origins, and gradually practicing more balanced emotional responses. This process often benefits from professional guidance, especially when these patterns stem from trauma or deeply ingrained family dynamics.

Resources for Continued Emotional Growth

Recommended books for emotional development include “Emotional Intelligence” by Daniel Goleman, “Permission to Feel” by Marc Brackett, and “The Gifts of Imperfection” by Brené Brown. Apps like Mood Meter, Daylio, and Insight Timer provide digital tools for emotion tracking and mindfulness practice. Therapy worksheets and emotion wheels offer structured approaches to emotional exploration.

Consider therapy or counseling for emotional support when you experience persistent emotional difficulties, recurring relationship problems, trauma symptoms, or significant life transitions. Mental health professionals can provide personalized strategies, safe spaces for emotional processing, and evidence-based treatments for specific emotional challenges.

Creating a personal emotional first-aid kit involves identifying specific strategies that help you cope with different types of emotional distress. This might include breathing exercises for anxiety, creative activities for sadness, physical exercise for anger, and social connection for loneliness. Having predetermined coping strategies makes it easier to respond effectively during emotional crises.

Building a support network for emotional wellness involves cultivating relationships with people who can provide different types of emotional support. This might include family members for unconditional love, friends for fun and distraction, mentors for guidance, and professional helpers for specialized support. Diverse support networks provide resources for various emotional needs and life circumstances.

Understanding and using a comprehensive feelings list represents just the beginning of your emotional development journey. As you practice identifying and expressing your emotions more precisely, you’ll likely discover subtle distinctions and patterns unique to your experience. Remember that emotional intelligence develops gradually through consistent practice and self-compassion.

The investment you make in expanding your emotional vocabulary and awareness pays dividends in every area of life. From deeper relationships to better mental health, from improved conflict resolution to enhanced self-understanding, emotional literacy provides tools for navigating life’s inevitable challenges with greater skill and resilience.

Begin today by simply noticing and naming one emotion you experience, however subtle it might be. With patience and practice, you’ll develop the emotional fluency that supports lasting well-being and authentic self-expression.

FAQs About the Feelings List

1. Why is it important to have a feelings list?

A feelings list helps expand your emotional vocabulary so you can better identify and express what you’re experiencing. Naming emotions accurately is the first step toward managing them in a healthy way.

2. How can a feelings list improve my mental health?

Recognizing emotions reduces confusion and prevents them from building up. It also makes it easier to talk about your feelings in therapy or relationships, which supports healing and connection.

3. Can children use a feelings list?

Yes! Feelings lists are a great tool for kids to learn emotional awareness early. Many parents and teachers use them to help children express themselves more clearly.

4. Why is it often harder for men to talk about feelings?

Cultural messages often teach men to hide emotions, which can make expressing them feel uncomfortable or “weak.” A feelings list offers a safe and simple way to start building that emotional language.

5. How can I practice using a feelings list daily?

Try checking in with yourself once or twice a day and pick a word that matches your emotional state. Over time, this practice strengthens self-awareness and emotional regulation.